There are some geologic features that are just way too cool for humans NOT to write a myth about them. The long-standing explanation of the columns of the Giants Causeway was that the giant Finn MacCool wanted to build a bridge to attack his rival in Scotland and that they destroyed the bridge in their fighting, leaving only the Causeway in Ireland and Fingal’s Cave in Scotland remaining. Then that long-standing story gets to rub shoulders with whatever geologic explanation comes along a few centuries later.

On this vacation, we got to road-trip to one of the most stunning geologic sites in Ireland – the Giant’s Causeway. While we were up there anyways we decided to check out the Carrick-A-Rede rope bridge too, where I got an unexpected extra dose of cool geology.

Giant’s Causeway is a phenomenal exposure of basalt. Sure, the rock type itself is nothing new. I wrote my thesis about basalt in northeastern Oregon. This particular basalt became famous for the huge field of well-exposed basalt columns, a feature that forms when lava gets the chance to cool slowly. And not only do you get to see the sides of the columns like you can in Oregon, but you can clamber over the tops of them too. It’s well worth the money for the audio tour. There are two versions for two different audiences- normal person and geology nerd – and both are entertaining and informative.

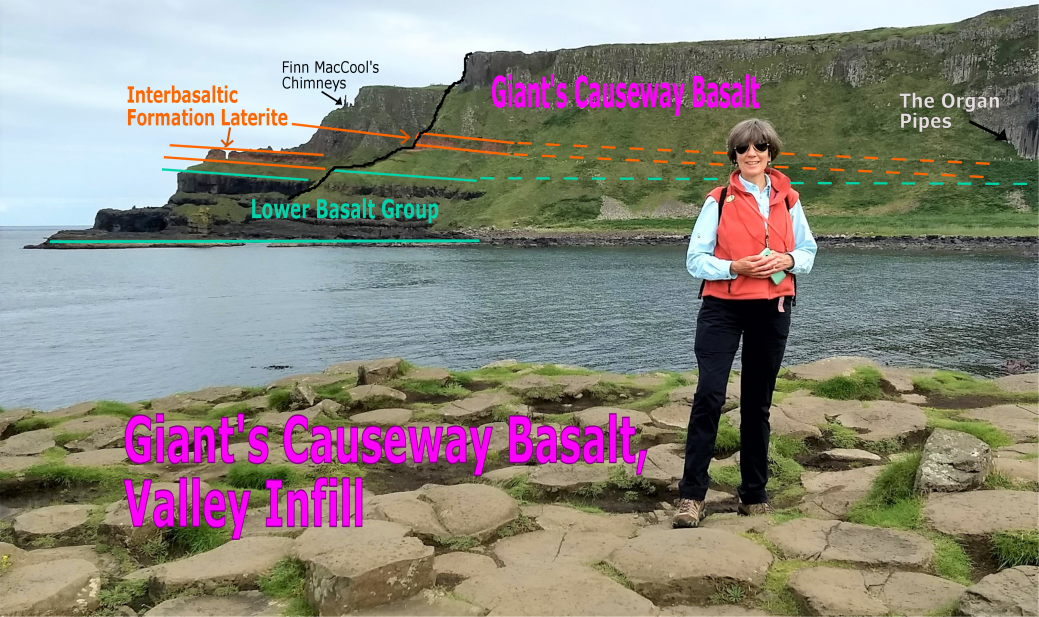

This basalt flowed out of cracks in the local limestone around 55 to 60 million years ago, when the Atlantic Ocean was opening up. It took two stages to create the landscape here. First, about 6 basalt flows spread evenly across the landscape. Then volcanism stopped for a while; there was enough time for a the top part of the basalt to be weathered a rusty brown color as chemical reaction changed the basalt to laterite, lithomarge and bauxite. This zone is called the Interbasaltic Formation here. There was also time for water to carve a valley into the landscape. Later, volcanism restarted and a huge volume of lava poured into the river valley! At the time of formation, this deposit would have been a lava lake 90 meters (295 feet) deep! We know it had to have happened all in one event, because there are no weathered layers within it.You can see a basalt cliff at the level of my head in the background of the photo to my right – that basalt was deposited on top of the plateau beside the river valley. The thickness of the lava in the river valley meant that it cooled quite slowly, allowing the formation of the regular 4 to 7 sided columns.

You can see what I just described in the photo below. Note that you can see all three layers behind my mom, but that she’s standing on the Giant’s Causeway basalt that flowed into the valley that was cut into the Lower Basalt Group.

My mom Lise, always the best tour guide, is here to introduce you to basalt geology! We didn’t hike up to the Organ Pipes, but they’re a beautiful exposure of both the colonnade and entablature layers of the Giant’s Causeway Basalt formation. Finn MacCool’s Chimneys are precarious free-standing basalt columns whose companions were eroded away on the headland.

Checking out the lower basalt groups – they were physically weathered into rounded shapes as groundwater percolated down into the formation. The fancy name for this is “spheroidal weathering”. You can see a little bit of the Interbasaltic group in the top left corner of the photo, where the dark gray basalt has been chemically weathered into orange/brown minerals.

Whether they’re the ones I studied in Oregon or the Irish ones in this post, basalt flows have a certain internal structure to them. It’s determined by the fact that the molten rock cools mostly from the top down, with a little bit of cooling driven by the cooler ground underneath the flow. The quicker a region of the lava cools, the smaller the size of the cooling features. Air or contact with underlying rock rapidly cooled the lava at the very top or bottom of the flow, giving it a crumbly texture. In the diagram below, these areas are the vesicular top and bottom. Just below the vesicular top, the rock was cooling more slowly. Small cracks propagated from the top of the flow downwards as the rock cooled and shrank. The rock was cooling just quickly enough that the pattern of cracks was somewhat chaotic, creating blocky shapes or the curved and twisting “fanning columns” in this “entablature” zone.

Illustration of a basalt flow interior with vesicular zones, entablature, and colonnade from: https://jgs.lyellcollection.org/content/157/4/715

At Giant’s Causeway you can see huge boulders from the entablature zone that have fallen down among the columns. They have kind of a “giant meatball” rubbly texture that contrasts with the smooth elegance of the columns but makes them easy to climb.

Below that is the sweet spot of cooling, whose features dominate the Giant’s Causeway. In the “colonnade” zone of the basalt flow the cracking pattern propagates neatly downwards. A hexagonal pattern develops when cooling contraction occurs at centers of mass that are evenly spaced in a homogeneous body of lava. If there are variations in the thickness or composition of the lava then other geometries of fracture may occur, with anywhere from 4 to 8 sides.

Giant’s Causeway’s famous colonnade layer, with geologist for scale.

You can see in the picture above that the columns are broken by joints perpendicular to the ones that define the columns. These are subtle ball-and-socket joints that formed when the area was subjected to horizontal stresses after the rock had cooled and the columns had formed. These ball-and-sockets allow the formation to bend a bit.

concave “socket” column top on the left, convex “ball” column top on the upper right.

Later that day the sun came out and we decided to check out the Carrick-A-Rede rope bridge. It’s absolutely touristy but worth it on a beautiful day like that. The bridge and island are only accessible by paying for a group tour that departs at regular intervals. You end up parking in a nearby abandoned limestone quarry called Larrybane Quarry. It has beautiful seaside views, and a fight scene from Game of Thrones was filmed here.

Unfenced drops? Cliff edges? Count me in. Spoiler alert, our mom did not keep us close…

How can you ask a geologist to stay on the path when there are cool chert nodules to investigate in sea caves? In the right-hand photo, the black rock is chert. In the photo with my sister and me in it on the left, you can see how these chert nodules are distributed in horizontal bands in the limestone. These nodules are formed after the remains of microscopic organisms like coccolithophores, radiolarians, and diatoms are laid down and start to solidify into rock. Water in the formation dissolves some of the silica-rich remains and redeposits them in layers around impurities in the sediment, forming blobs of chert that are often called “flint” when they’re found in chalk beds like these.

In the top right corner of the photo you can see stalactites – this is the only known location in the Ulster Limestone (a.k.a. Upper Cretaceous Limestone) along the Causeway Coast with these distinctive formations.

When the line of tourists waiting to get across the bridge is longer than the bridge, it might be a tourist trap.

This was just a detour to the main attraction – the Carrick-A-Rede rope bridge. It was constructed in 1755 to allow fishermen access to fruitful salmon fishing groups, and has been developed as a somewhat oversold tourist attraction. It has a neat geologic history though. The little island stands tall because it’s the eroded neck of a volcano! It formed 62 million years ago, just a little bit before the basalt at the Giant’s Causeway. The island is formed of dolerite, a kind of intrusive volcanic rock. When you’re on the island and looking back to the mainland, you can see large blocks of basalt and limestone suspended in a matrix of volcanic ash.

The short hike to the bridge takes you down rocky staircase and along gravel paths with lovely views out to sea. The tour guides don’t encourage the group to spend too much time on the island itself, but we got to take twenty minutes or so to spy on the seagull nests, eat some snacks, and admire the view out to Rathlin Island.

Here’s a map of an overview of the geology around Giant’s Causeway and Carrick-a-Rede that I put together in ArcMap. This is from the 1:500,000km shapefile available from the Geological Survey of Ireland. The more detailed 1:100,00K map excludes Northern Ireland… I guess political animosity somehow spilled over into data collection and sharing here. That’s a shame. So Carrick-A-Rede itself isn’t mapped here.

Stay tuned for a geology/archaeology crossover event! My family headed to the Newgrange Stone Age Passage Tomb later that week.

Resources:

https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/GeositesGiantsCauseway

booklet on the geology of Northern Ireland’s Coast: http://ccght.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/geology_booklet.pdf

A field trip at the Sand Atlas blog whose author took some better photos of the formations: https://www.sandatlas.org/giants-causeway/

Debbie Hanneman over at GeoPostings did this trip back in 2017 and shared some great photos: https://www.geopostings.com/category/giants-causeway/

AGU resource on columnar jointing: https://blogs.agu.org/georneys/2012/11/18/geology-word-of-the-week-c-is-for-columnar-jointing/

Information about the geology at Carrick-A-Rede: http://www.habitas.org.uk/escr/site.asp?item=1145

Article about the formation of chert nodules in carbonate beds:

Maliva, Robert G., and Raymond Siever. “Nodular Chert Formation in Carbonate Rocks.” The Journal of Geology, vol. 97, no. 4, 1989, pp. 421–433. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30078348. Accessed 14 May 2020.

Cool podcast about the tiny creatures that become chalk, courtesy of Radiolab: https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/radiolab/articles/190284-war-we-need

Great post 😁

LikeLike

An excellent blog! I’m glad you enjoyed your visit to my home county. Just to let you know, you can access 1:10,000 scale geology maps of NI online here: http://mapapps2.bgs.ac.uk/GSNI_Geoindex/home.html

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the lead, Alastair! I look forward to exploring those. Thanks for stopping by! 🙂

LikeLike